Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The majestic Himalayas, born from the tectonic collision between the Indian and Eurasian plates, cradle ancient tales in their snow-covered peaks. These tales echo through the rivers and streams that have shaped civilizations and landscapes for thousands of years. Among these, the Saraswati River stands as both a historical reality and a mythological marvel, intertwining the natural and the divine.

THE DAWN OF RIVERS AND CIVILIZATIONS

During the Early Holocene, some 7,000 years ago, glaciers melted under a warmer climate, giving birth to rivers like the Saraswati, Sutlej, and Yamuna. The Saraswati, a glacier-fed giant, flowed mightily from the Bandarpunch Mountain (Valdiya, 1996), confluence of the Saraswati-Rupin Glacier in Uttarakhand, carving through the northwestern plains.

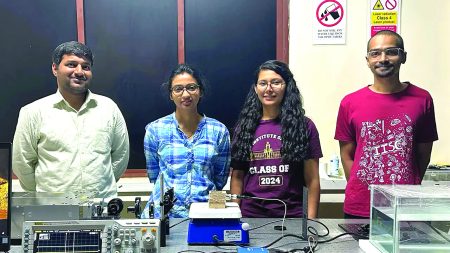

According to the Rigveda, the Saraswati is “pure in her course”, sustaining land and life, and is referred to as “Naditama”, the greatest of rivers, flowing from the mountains to the sea (Rigveda 7.95.2). The early villages of Rakhigarhi, Kalibangan, and Banawali reflect this spirit. The river was revered not only as a physical waterway but also as a divine entity, essential for spiritual practices and rituals. The Ramayana highlights the Saraswati as a fertile eastern river critical to early Aryan settlements. The Puranas mention the Saraswati merging spiritually with the Ganga and Yamuna at the Triveni Sangam, keeping its divine legacy alive. Such accounts resonate with modern scientific studies that use satellite imagery to trace the paleochannels of this lost river. Our discovery depicts a large paleochannel of 1.6 km width and more than 40m deep, studied based on bore-hole data and during the Metro Rail excavations. The TL-dating gave an age of approximately 5 ka linking this paleochannel thought to be part of the river basin near Nigam Bodh Ghat-Delhi flowing in the eastern direction.

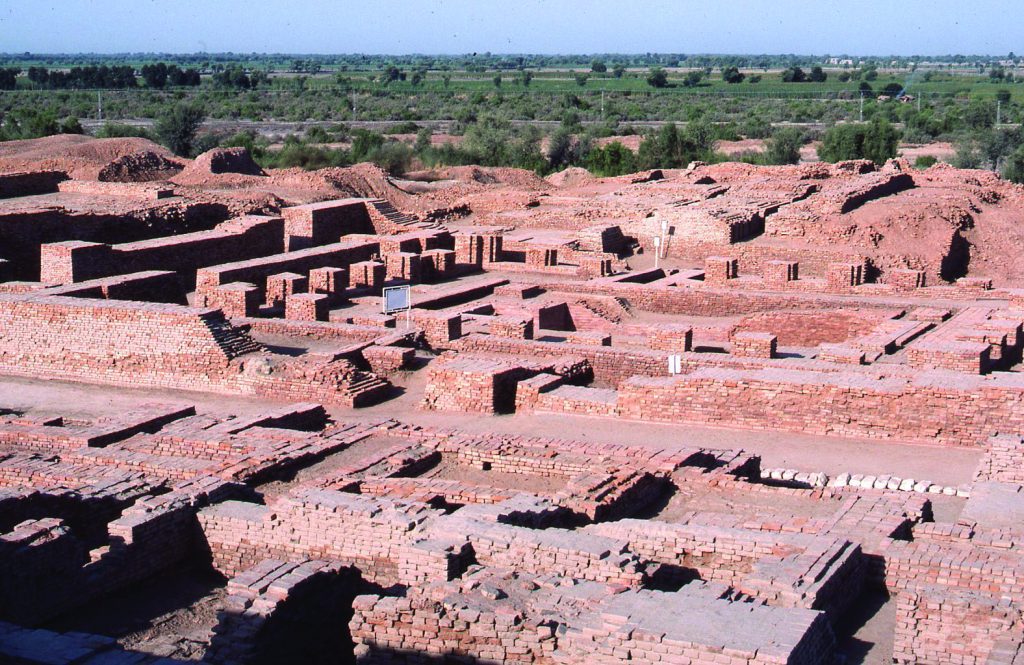

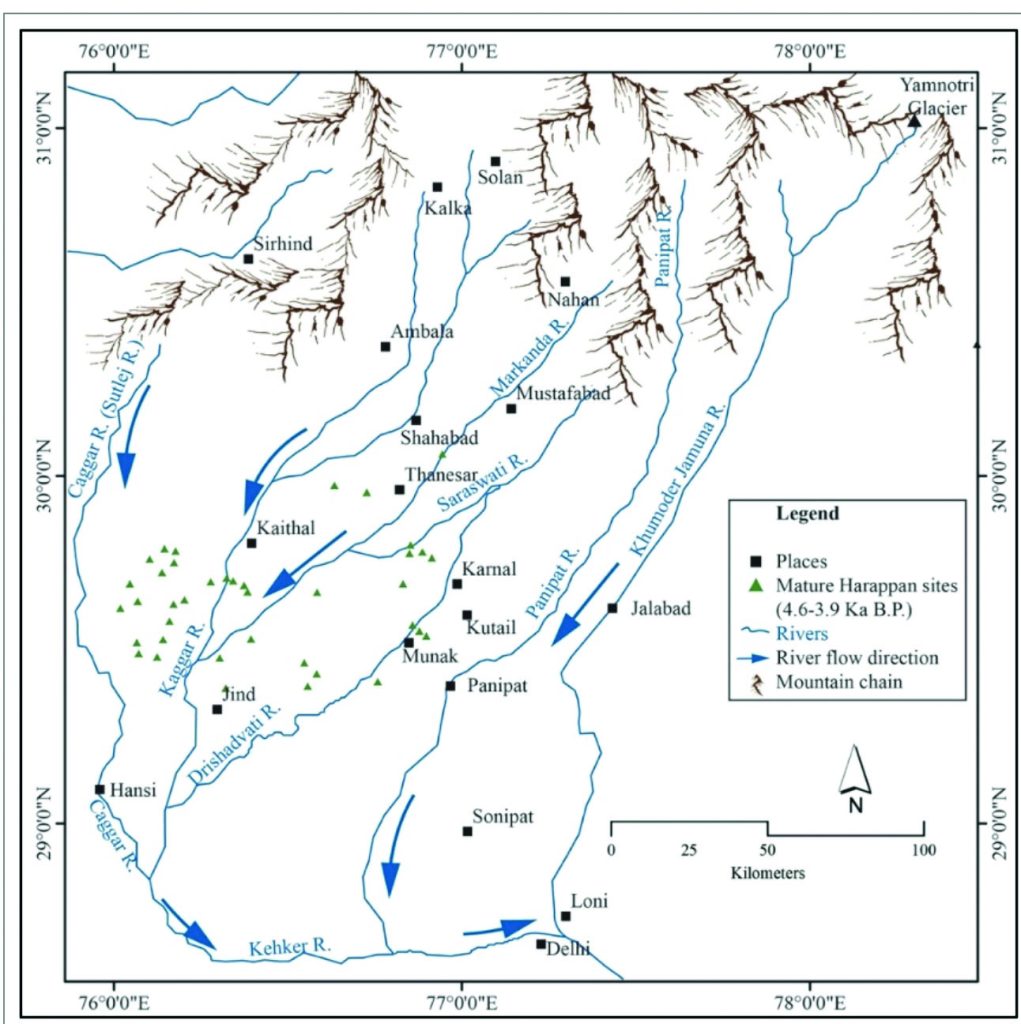

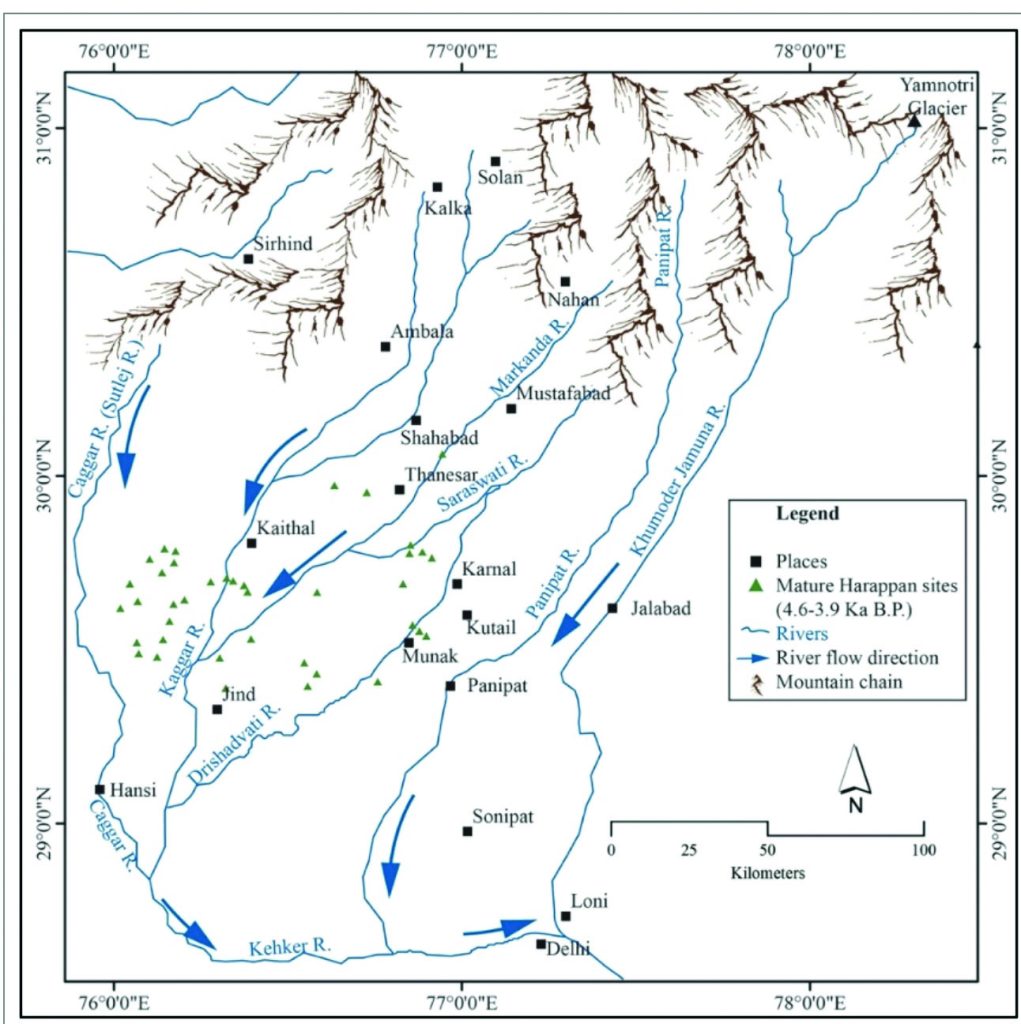

The Sutlej-Ghaggar-Saraswati- Drishadvati basin witnessed the rise of a prosperous civilization. These waters, originating in the Himalayas, created a cradle of civilization stretching from the eastern highlands to the western lowlands. The Golden epoch of the eastern basin (7000 BCE – 2600 BCE) flourished due to the Holocene Climatic Optimum with warmer and wetter climate, marked by monsoonal stability and glacial melt.

Mythology and science work together to reveal these rivers’ fates. According to Puranic narratives, the warmer and wetter environment of the Holocene Climatic Optimum, which occurred approximately 5000 BCE, brought agricultural prosperity. The Brahmanda Purana mentions how the Saraswati flowed with abundant waters, enriched by the Shutudri (Sutlej) and Yamuna before tectonic upheavals altered their courses. Settlements flourished, with Bhirrana, one of the oldest Harappan sites, marking agricultural innovation. Rituals at sacred sites likely honoured Saraswati Devi, aligning with the description of rivers as divine lifelines in the Atharvaveda flowing in the eastern direction but the earth beneath these cities was restless.

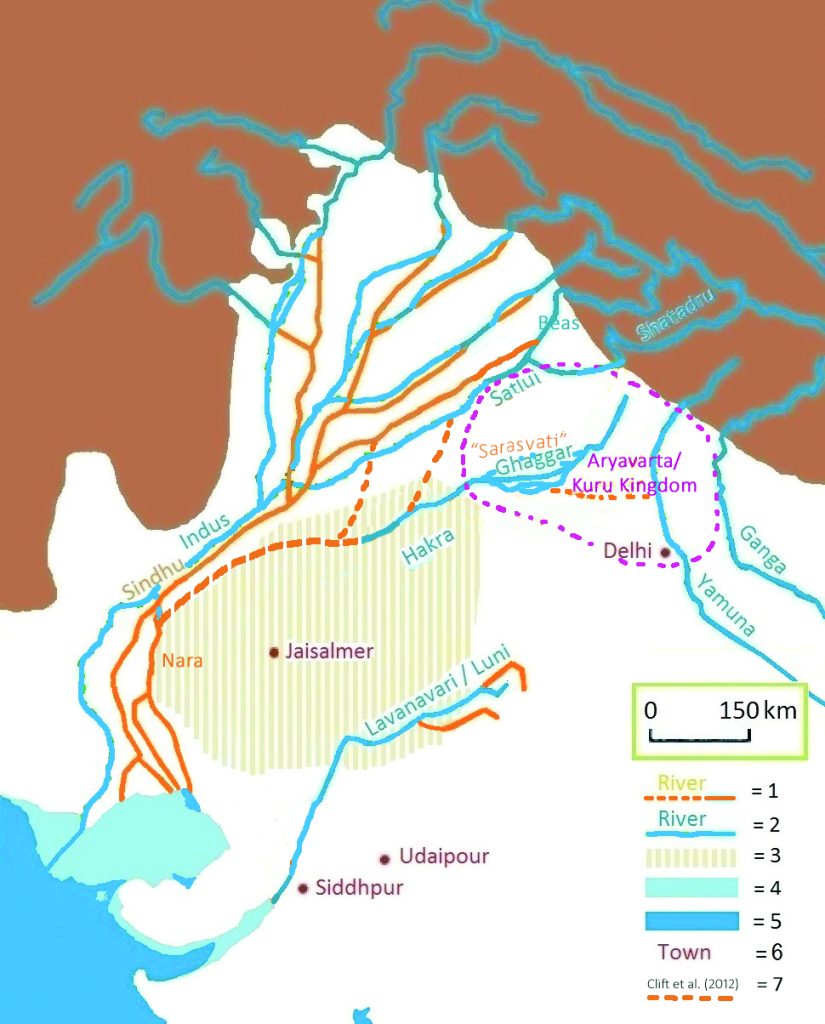

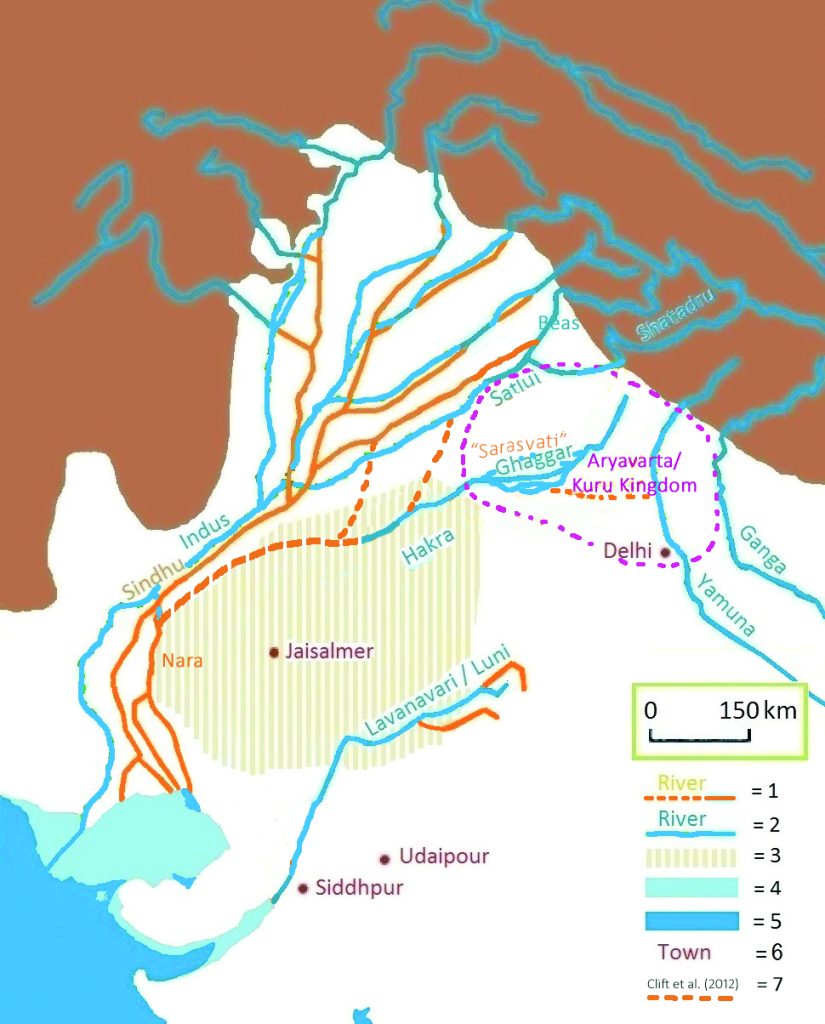

The tectonic uplift, folding-faulting of the Himalayas and the Himalayan glaciers retreat shifted the water courses upward in the north or in the west or east sides, shifting the directions and changing river habitat from perennial to seasonal rivers. Challenges began around 3000 – 2600 BCE and by 3000 BCE, signs of trouble began appearing. Monsoon patterns grew erratic, and the Saraswati’s waters diminished. This shift aligns with the Mahabharata’s account of the river “disappearing at Vinasana” in Haryana. The epic depicts a once-mighty river fading into memory, yet retaining its sanctity through sacred rituals performed along its dry bed. The Ghaggar’s paleochannels, traced via remote sensing and satellite imagery, map the path of a river that once surged with Himalayan waters but now vanishes into the Thar Desert. The Drishadvati’s course, similarly ephemeral, ebbed away, leaving behind traces in the sands and stories in the Vedic texts.

As the rivers shifted, so did civilizations. The Saraswati-Ghaggar basin cradled some of the most significant Harappan sites. The Harappans adjusted as the Saraswati weakened. A late Harappan engineering marvel with advanced reservoirs and water management, Dholavira, which is perched on the border of the drying river, became a testament to their inventiveness and human resilience. Important events, such as Balarama’s trip, where he followed the river’s waning flow to its terminus in the desert, are depicted in the Mahabharata along the Saraswati. These stories highlight the river’s spiritual and cultural significance despite its degradation. The Saraswati was preserved in the collective psyche through the performance of Vedic rituals at locations like Kurukshetra.

Climatic disturbance and shift (2600 BCE – 1900 BCE) along with erratic monsoons and droughts due to sudden reduction in monsoon rainfall and colder, drier conditions reduced river volume, affecting agriculture and trade. Harappan cities faced water scarcity and began losing their dominance. The Harappans reached their peak, between 2600 and 1900 BCE with urban centres like Mohenjo-Daro, Dholavira, and Harappa rising along western rivers such as the Indus and the now west-flowing Sutlej.

Scientists now link the decline of the Saraswati to climatic shifts around 1900 BCE. Weakened monsoons and recurring droughts parched the basin. River piracy compounded the crisis, as the Sutlej and Yamuna diverted their waters. The Saraswati’s drying led to a migration towards the Ganga-Yamuna doab, heralding the decline of the once-thriving Harappan cities.

Climate change may be one of the primary drivers for the decline of Harappan civilization (1900 – 1600 BCE), however, the civilization could not sustain the hydro-geomorphic realignments, triggered by the tectonic upliftment and folding of Main Himalayan Thrust (MHT). This facilitated diversion of Sutlej towards the west, and its joining of the Indus system through river piracy. Similarly, the Yamuna was captured by the Ganga, and diverted to the east. This dual piracy severed the eastern basin, further weakening Saraswati’s flow into the Ghaggar-Hakra channel. The Vayu Purana and Matsya Purana describe this as a pivotal event marking the transition of civilizations. The Ramayana, though later, references Bharata’s journey along rivers like the Saraswati to reach Ayodhya, emphasizing the river’s lingering significance. Settlements migrated eastward towards the Ganga-Yamuna Doab, as evidenced by late Harappan sites such as Hastinapur. Yet, nature’s trials persisted. The weakening of monsoons, likely influenced by global climatic shifts, brought recurring droughts. These, coupled with tectonic upheavals like the earthquakes during the period 2600-1800 BCE (Grijalva, K. A. et al., 2006), compounded the challenges. Excavations at Harappan sites have revealed structural damage (like Mohenjo-Daro and Rakhigarhi) and shifts in settlement patterns that align with the timeline of tectonic disturbances. The Saraswati, once the life force of the eastern settlements was now a memory replaced by smaller, rural communities scattered across the Ganga-Yamuna doab.

Today, remnants of the Saraswati spark debates and dreams of revival. Archaeologists excavate her dry bed, unearthing pottery, beads, and fire altars. Satellite imagery continues to trace her paleochannels across Haryana and Rajasthan. The Saraswati Revival Project seeks to reawaken this lost ancient river by linking its paleochannels to modern canals, blending historical reverence with technological innovation. This endeavour offers a fusion of history and optimism by bringing together ancient writings and modern science.

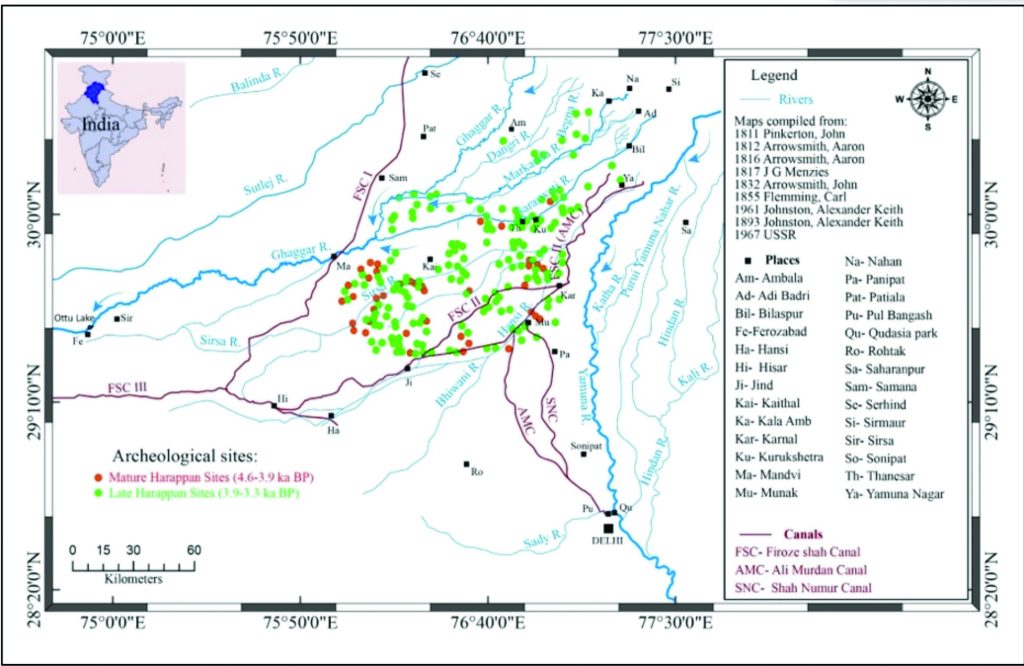

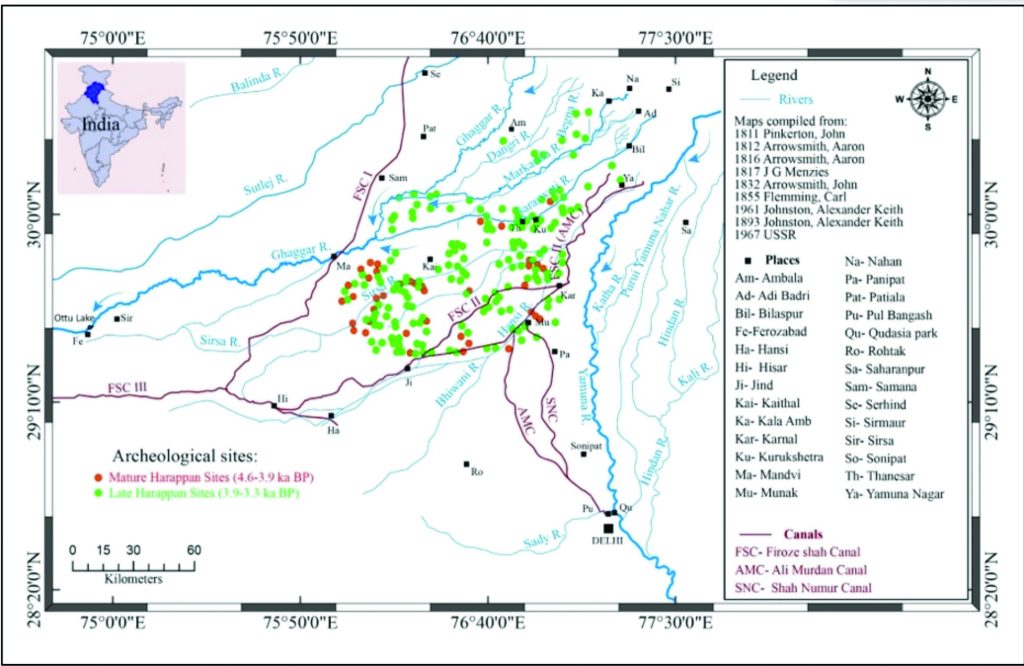

Maps Courtesy: Prof Chandra Shekhar Dubey, Dr Gonmei Zenus Piuthaimei, Prof Shashank Shekhar

The Saraswati’s story of grandeur and collapse is echoed by the Ghaggar river, a seasonal thread in the desert. We are reminded by the Sutlej, Yamuna, and their tributaries that rivers are more than just waterways; they are lifelines that influence the course of human history. Therefore, the rivers of Sutlej, Ghaggar, Saraswati, Drishadvati, and Yamuna present a story of change—of the interaction between nature and civilization—from the Himalayan glaciers to the dry sands of the Thar. Whether scientific or mythical, their flow never stops illuminating and inspiring humanity’s journey. Even after its decline, the Saraswati remained central in cultural memory. In the Tandya Brahmana, the river was declared spiritually alive in its subterranean form. This aligns with modern scientific discoveries of paleochannels under the Thar desert. Communities adapted to seasonal flows of the Ghaggar-Hakra, relying on subsistence agriculture and smaller settlements. Sites like Banawali show evidence of resilience in the face of environmental challenges.

A TALE OF ADAPTATION AND RESILIENCE

The Saraswati’s rise and fall reflect humanity’s dependence on climate and natural systems. Similarities with contemporary crises (droughts, flooding, migration) remind us of the need for resilience and sustainable resource management. However, in the present era, man-made constructions and destructions from 12th century to the present have further aggravated the natural river basins to canal systems and further drying being converted to drainage into sewerage (e.g. Saraswati Nala). The case of Sutlej-Ghaghar-Saraswati-Drishadvati basin is a testimony of destruction of such large basins into a future dry desert land due to canal systems.

Anthropogenic impacts on the area’s water system were initially noted under Firoz Shah Tughlaq’s rule (A.D. 1351 to 1388). The construction of a canal system that split off from the main rivers for irrigation and other uses was the first step in the artificial disruption of the landform. In order to construct a massive reservoir at his fort Hissar Feroza, he trenched all rivers between the Sutlej, Ghaghar, Markandey, Saraswati (Sursutti), and Drishadvati. He also captured and constructed a canal from Sirhind to Hissar fort and another from Yamuna to Hansi and further to Hissar Firoza, i.e., the present-day Western Yamuna canal. This canal system had been confining the courses of rivers. The drier climate and seasonal rivers were further disturbed by manmade diversions along with the 1803 Garhwal earthquake, culminating in an unmaintained drainage system. Moreover, canal reconstruction continued under several rulers (like Shah Jahan) and the British regime, and it continues even today. Some of these canals were aligned along the paleochannels of rivers or along seasonal rivers. Along with such anthropogenic forcings, the watersheds were disrupted by several transverse tectonics in the recent geological times, leading to river water diversion. The rivers started dying, and their courses were either aligned by a canal or a drain.

The Saraswati is a symbol of nature’s grandeur and humanity’s resilience from its glacial origins to its mythological reverence. It bore witness to the rise and fall of civilizations, shifting riverscapes, and climatic upheavals. The rivers of the Saraswati basin, through history and geology, tell a story of adaptation in the face of constant change—a reminder that while rivers may change course, their legacy flows eternal. The Saraswati basin’s story isn’t just one of loss; it’s a narrative of adaptation and the enduring relationship between geography, mythology, and human innovation. The east-to-west shift epitomized civilization’s ability to overcome calamities like earthquakes, river piracy, and climatic upheavals, leaving lessons deeply engraved in both mythology and science.

* Prof C S Dubey is Executive Director, NORMI Research Foundation and former Vice Chancellor, KR Mangalam University, Gurgaon, Haryana, while Dr Gonmei Zenus Piuthaimei is a research scientist at NORMI Research Foundation and Prof Shashank Shekhar is a professor at the Department of Geology, University of Delhi.