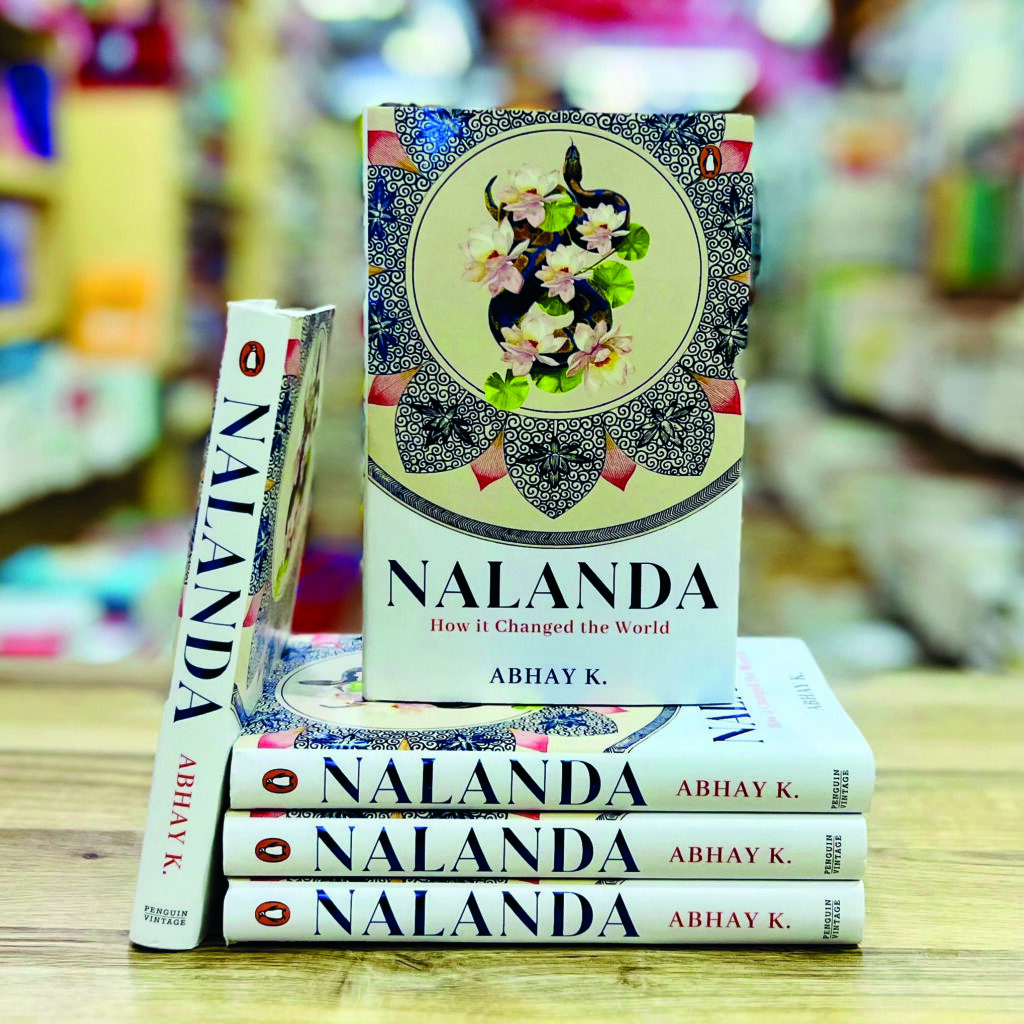

NALANDA: HOW IT CHANGED THE WORLD

Abhay K

Penguin Random House,

Gurugram, India 2025,

Pages 193,

Price Rs 699/-

BOOK REVIEW

Nalanda is one such site in India that evokes a deep sense of reverence for the legacy of knowledge that every Indian has inherited. Any visitor to Nalanda cannot remain untouched by the grandeur and magnificence of the place and the palpable cultural history that makes it one of the greatest seats of learning that continued from the 3rd century BCE to almost 14th century CE, for more than a thousand years. Nalanda stands as a counter to all the imperialist allegations of ignorance and illiteracy prevalent in India, which, as they said, was devoid of any respectable and worthy knowledge traditions. In writing this book, Abhay K, the author—the youngest Indian diplomat, with several academic interests like translations, poetry and painting—has contributed a timely and ambitious work that seeks to reintroduce the readers to the intellectual, spiritual and global legacy of Nalanda. This review focuses on the book’s contribution towards understanding the scientific traditions prevalent in Nalanda and how this knowledge impacted the world.

The book is divided into eight thematic chapters, framed by an evocative introduction and exhaustive endnotes. Each chapter is devoted to a key theme and explains the origin and rise of Nalanda, its luminaries, visiting foreign scholars, its decline and devastation and finally, its global footprint. The author combines historical narrative with anecdotes, legends and poetic interventions, giving it the feel of a personal journey told with love and belongingness. It is explained by the fact that he was born in Nalanda and had roamed among its ruins in his childhood, dreaming of a day when the University will rise from its dust. His dream came true when Nalanda University was established in the year 2010 in the nearby Rajgir or Rajgriha.

We have known Nalanda as a Mahavihara where philosophy and religion were discussed, where Buddhist monks in robes meditated on the existential questions of life away from the material world. However, it was also in Nalanda that several great scholars resided and worked in the myriad domains of science such as medicine, public health, mathematics, astronomy, alchemy, ophthalmology, public health, metallurgy and architecture.

Enquiries in science also included developing the method of science. Scholars at Nalanda like Nagarjuna and Vasubandhu contributed to advancing the recursive argument method which further led to the development of the medieval scientific method—an approach later adopted by Central Asia, the Arab world and Europe.

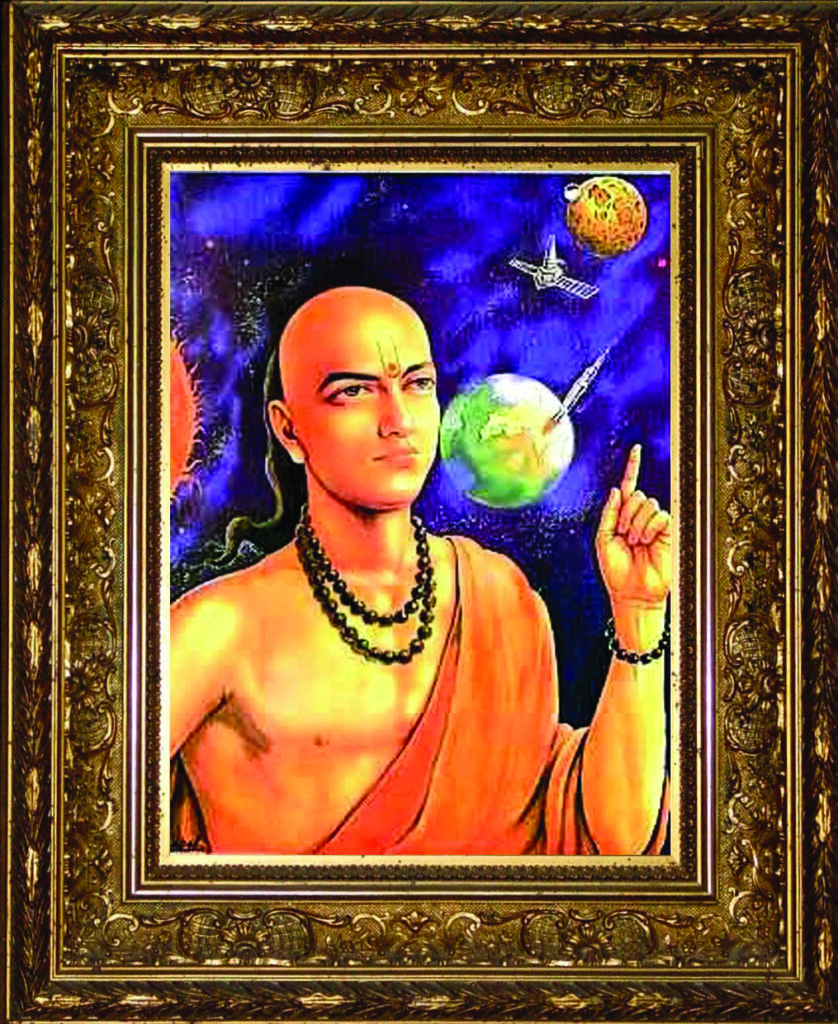

Aryabhata, the father of Indian mathematics was the most prominent mathematician at the Nalanda Mahavihara in the sixth century CE. He wrote the treatise Aryabhatiya and was the first mathematician to assign zero as a digit, a concept that simplified computations, leading to the development of the domains of algebra and calculus. His innovative work in extracting square and cubic roots and applications of trigonometric functions is noteworthy. He was the first to observe that the Earth revolves around its own axis and was able to calculate the value of ‘pi’ to the fourth decimal point.

The author writes in the book: ‘The history of the scientific genesis of the medical system indicates that the shift from the religio-magic to an empirico-rational system began under the leadership of the Buddhist monks. The modalities of taking care of the health of the fraternity of the monks and nuns developed here.’ The institution of Nalanda played a significant role in advancing the practice of medicine, which was initially founded by Jivaka, the physician of King Bimbisara and also of the Buddha. Vagabhatta’s Ashtangahridaya was the medical treatise taught in Chikitsa Vidya at Nalanda.

The Rasaratnakara, a treatise on Indian alchemy composed by Nagarjuna in Nalanda was a work that explains chemical processes and purification processes of minerals like silver, sulphur, copper, pyrites, gold, mica, etc. The world’s first printed book, published in China, is The Diamond Sutra—a part of Prajnaparamita Sutra—was also written by Nagarjuna at Nalanda.

Image Courtesy: Pixabay

Nalanda also became a major centre of art and artworks in stucco and metal were produced here. Metal art was prevalent as the region had inexhaustible sources of iron ore. It has been documented that ‘metallurgy as an art form was an integral part of the Mahavihara’s curriculum. This is indicated by the presence of a brick-lined smelting furnace to the north of Site no.13 and a large volume of metal figures recovered during excavation.’ The flourishing art traditions, thus, were supported by a robust foundation of science and technology which facilitated the art renderings by creating tools, providing materials and refining technology for creative expressions.

The development of the quadrangular vihara and the formation of the Panchayatan Chaitya remains Nalanda’s foremost contribution to the sphere of architecture. Nalanda’s excellence and best practices in medicine, ophthalmology, alchemy and other health sciences were embraced in Tibet, Nepal, China, Korea, Japan, Mongolia and many other parts of the world.

Nalanda must also get the credit for the development of book culture, which democratised knowledge. Development of the art of manuscript writing, illustration, preservation and copying at the Mahavihara contributed to a knowledge-centric society much needed for the development of scientific thoughts.

Apart from writing treatises, experimenting and passing on the knowledge to young students, Nalanda also provided infrastructure, administrative support, and a cultural scaffolding for thriving science domains. The book gives a glimpse of intellectual life, universalism and freedom of beliefs practiced in the Mahavihara. It is heartening to know that ‘intellectual and philosophical differences were a cause of celebration and monks had the freedom of thought, expression and belief. It provided an atmosphere of freedom and tolerance where any dispute could be settled through debate, using the recursive argument method’. It is not for nothing that an argumentative tradition was always prevalent in India, which even after a long suppressive foreign rule could not be completely erased from the nation’s psyche. It is this tradition which helped the scholars to take long strides in various scientific domains without any fear of persecution which was witnessed in Western cultures.

Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Though we have been told that the vision of a university was a Humboldtian idea first conceived in Germany, it is quite evident that Nalanda with its ‘well laid out plan with multiple monasteries, large endowments, a walled residential complex, international students, foreign scholars and where a variety of disciplines were taught by the best teachers’ was the original blueprint which was later followed for the universities in Central Asia, Europe and the rest of the world. Thus, Nalanda’s impact is felt today in far corners of the earth and in unimaginable ways.

In the chapter on the luminaries of Nalanda, the author introduces the life and works of 27 scholars who lived and worked at Nalanda and immortalised their names with their seminal contributions in their respective domains, transforming the landscape of Asia and the world. Another chapter on foreign scholars records the lives of 30 knowledge seekers who congregated at the steps of Nalanda ‘from the northern land route from China, Korea, Tibet, Nepal, Central and West Asia and the southern sea route via Java, Sumatra, the straits of Malacca, Burma and Arakan’. The legends associated with these historical figures illustrate the richness of our traditions and allow us to imagine their times in vivid detail. The brief descriptions provoke the reader’s curiosity to know more about their illustrious lives. Production of these stories in other formats such as popular films could be entertaining as well as educating, and could reach a wider audience and can be a solution to our ignorance towards our legacy.

While not a conventional academic historian, Abhay K has shown considerable skill in weaving together disparate sources such as Chinese chronicles, Sanskrit treatises, travelogues, archeological reports and modern scholarship. Bringing the contemporary into the narrative, the author is able to remind the reader of the honorable presence of the treasures of Nalanda enriching India’s affairs even in the present times.

The book’s short format, though engrossing and easy to engage with, lacks the depth of exhaustive research. While the narrative is rich and textured, some historical nuance is lost. At places, repetitions mar the flow. Otherwise, the book is an engaging read and can be enjoyed by laypersons as well as used as reference by researchers and scholars in the field.

What distinguishes the book is its placement of Nalanda as a site of world-historical importance, where practice of science, development of scientific methods, advancement in different branches of science went unhindered for a substantial period in history. However, this global placement does not ignore the specifics and the book traces how Nalanda evolved out of early Buddhist monastic traditions and royal patronage and how it sustained itself over centuries by adapting to political, doctrinal and social changes. Yet, the book is not merely nostalgic. It subtly critiques contemporary India’s ambivalence towards its own intellectual heritage and calls for an active revival of its civilizational confidence. At a time when there is a renewed interest in reviving ancient Indian knowledge systems, decolonising curricula and building India-centric perspectives, the revisiting of Nalanda offers a compelling read and enough food for thought about our rich legacy and our apathy to familiarise ourselves with that treasure.

*The writer teaches at Panjab University, Chandigarh, and is Programme Director, UGC-Malaviya Mission Teacher Training Centre at the University.