Image Courtesy: PIB

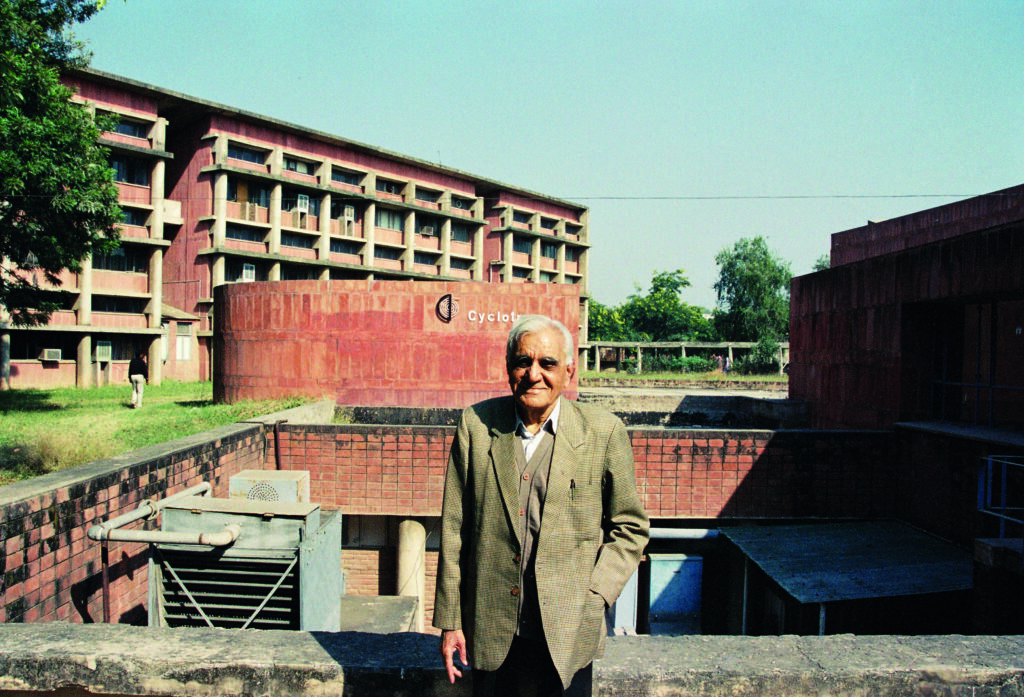

Cyclotrons occupy a special place in the history of experimental physics. Ernest Lawrence invented the cyclotron in 1929-30 at the University of California, Berkeley, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1939. Today, there are more than 1500 cyclotrons all over the world and 25 of them are in different institutions in India. However, one of the world’s oldest cyclotrons, created by Lee Du Bridge and Sidney Barner at the University of Rochester, New York, in 1936 and which is still operational stands proudly at the Department of Physics in Panjab University, Chandigarh. The story of how the vision of one Indian scientist, Prof Harnam Hans (1922-2014), made this feat possible is both incredible and inspirational.

HOW INDIA GOT ITS FIRST ACCELERATOR

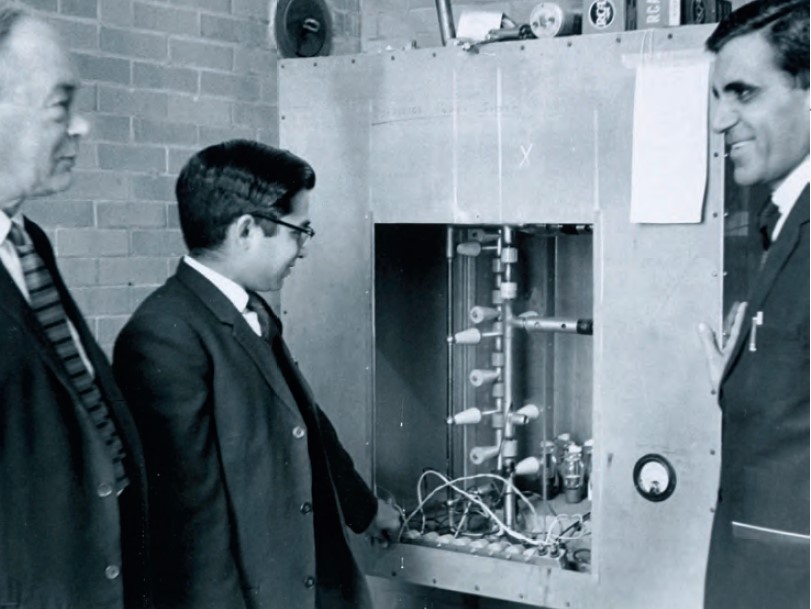

Dr Hans, born in 1922 in Multan (now in Pakistan), had graduated from Panjab University, Lahore, in 1945, Witnessing the rough times of partition which affected his family too, who shifted to Moga, in Punjab, and overcoming all constraints he did his post-graduation in Physics from Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi. While he was doing his PhD at Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, he visited Swarthmore, USA, for working on his experiments. There he came across and became so interested in accelerator based nuclear physics research—an upcoming field of the times—that he brought components of Cockroft-Walton type accelerator and successfully built and installed it at AMU in 1958 with the help of his colleagues Dr D C Sarkar and Dr C S Khurana. At that time, the government was focussing more on research institutes, and granting funds for cutting edge research equipment in the universities was not a priority. The accelerator at AMU was the first of its kind in an Indian university. From 1958-62, Dr Hans worked at AMU as Reader and through his deep passion and fearless approach made the department an active centre for high quality research.

Image Courtesy: PIB

In 1962, he moved to Texas A&M University as Faculty and later was deputed to Argonne National Laboratory at Illinois. In 1964, Dr Hans came to know of an interesting proposal regarding the world’s third cyclotron which was installed at the University of Rochester, New York.

A new Tandem accelerator of higher capacity was replacing the old cyclotron which had been used for research for about three decades from 1936. Instead of scrapping the machine, it was decided to put it up for donation free of cost. The idea was to put it away as legacy equipment which could grace a science museum.

A MONUMENTAL PERSONAL PROJECT

Dr Harnam Hans, who was well known for his fearless and unconventional approach, saw in this an opportunity for research in nuclear physics in an Indian university, and approached the University of Rochester for accepting the cyclotron and getting it shipped to India.

Accepting the donation of the cyclotron meant leaving his thriving research and teaching career in America, finding a job in an Indian university in India, getting permissions, cutting through red tape, crossing bureaucratic hassles, dismantling the machine, shipping it to India, getting someone trained on its working, reassembling and installing it. Dr Hans’s decision seemed to be risky, foolhardy and as his son, Vikram Hans says, ‘an audacious step’. It did not have the government of India’s backing, nor the American government’s patronage. It was a personal project, a labour of love for Dr Hans who was, nevertheless, fuelled by conviction for creating such scientific facilities in India, which faculty and students of India cannot even dream of. Having seen the multiplier impact on research of establishing the much smaller accelerator at Aligarh, he could vouch that this cyclotron in any Indian university would help initiate a culture of accelerator-based nuclear science research and result in many publications in nuclear reactions and nuclear spectroscopy domain by Indian researchers—something which India, barely 20 years into independence—badly needed. With his passion for science, Dr Hans was sure that hands-on experience of a machine of such import will definitely attract students to pursue its study. At that time India had three cyclotrons, in Kolkata, Bengaluru and Mumbai, and Dr Hans realised that the next one needed to be established in the northern region of the country.

He secured a teaching position in 1965 at Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra, Haryana and with the active help of his PhD student Inder Mohan Govil, Dr Hans was successful in bringing the machine to Kurukshetra. Though within two years he joined as Professor and Chairperson of Department of Physics, Panjab University, Chandigarh, and brought the machine to its sprawling campus in 1967. For this transportation and installation, he sought and received support from Dr Homi J Bhabha, Secretary, Department of Atomic Energy and Chairman, Atomic Energy Commission; Dr Raja Ramanna-a physicist working at Atomic Energy Establishment Trombay and Prof DS Kothari, Chairperson, University Grants Commission (UGC). The shipping cost from New York to Mumbai was borne by the University of Rochester while the UGC fully funded the installation cost of the cyclotron and sanctioned special staff positions for its operation and maintenance.

The ordeal was not over yet. After the machine was unboxed, the assembling of the machine became a herculean task, because no one in the region had the experience or exposure of even seeing a cyclotron, let alone working on it. The machine parts remained unassembled and non-functional for years. Unkind comments from disgruntled administration were natural consequences as the machine was called white elephant and was a waste of time, effort and money. The engineers, technical officers, lab technicians, PhD- and Post-Doctoral researchers were finally able to extract a beam of electrically-charged particles for experiments in 1977, and since then the cyclotron has been working, for the last almost 50 years. This feat is akin to a miracle as the rebirth of a cyclotron was a feat of perseverance and patience.

The cyclotron, though no longer an instrument for high end research, is still quite good to carry out experiments in basic nuclear physics, replicate earlier experiments for training purposes, and for applications in material sciences. In the early years of its functioning, the team published the largest number of papers globally on techniques in experimental nuclear physics to probe the electromagnetic aspect of nuclear structure. Researchers from the region continue to work on the accelerator for their PhD experiments, which may not provide breakthroughs, but still provides robust research outcomes in probing nuclear structure, test detectors, and sometimes to create short-lived isotopes for research. Students trained at the facility get placed in premier research institutes like Bhabha Atomic Research Centre and the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research. School students in hordes visit and witness the cyclotron first hand and see for themselves how a two-dimensional textbook diagram functions in the real world. Under-graduate and postgraduate students learn physics with the machine in the backdrop. Since its installation several technicians, mechanics, engineers, students, researchers and faculty members have cared for the machine, repaired it, oiled it and coaxed it to work.

Dr Jahnavi Phalkey, science historian, who has produced a film on the Panjab University cyclotron called it a ‘people’s story’. Staff, students, faculty, ordinary citizens, who have studied in ordinary schools and colleges who by happenstance got to be associated with this piece of history, a centrepiece of applied physics—talk about it not in a dry, objective way but in an emotional tone, pride, mixed with affection, wonder, awe, sense of duty and belongingness, as if the cyclotron is akin to an old grandparent, a little erratic sometimes, grudging, demanding love and care, but still going on. The domed ceiling of the building where cyclotron is located has become a proud landmark in the mental map of the department. A research culture has thrived and flourished.

It is quite evident that Dr Hans’s vision has fructified and his conviction has proven to be correct. Vikram Hans recalls his father telling him to ‘dream big’. Dr Hans, in fact, showed not only how to dream big but also how to make big dreams—as big as a cyclotron at an Indian university—turn to reality. The story of the cyclotron at Panjab University is not just about hardware; it’s about Dr Hans’s ingenuity and audacity, going beyond the call of duty, sacrifice for institution building, and his incredible effort to fulfil a promise for science in India.

*The writer is a professor at Panjab University, Chandigarh, and Programme Director, UGC-Malaviya Mission Teacher Training Centre in the University.