Image Courtesy: Dr Naveen Kumar

Lumpy Skin Disease (LSD) might sound like something out of a science fiction novel, but for farmers, especially in India, it has been a very real and devastating threat. First noticed in Zambia, Africa, back in 1929, the disease stayed in the African continent for decades. But in the late ’80s, it crossed borders—reaching Egypt in 1988 and Israel in 1989. Over time, it spread across the Middle East, Europe, and more recently, parts of Asia, including India.

LSD is a viral disease that affects cattle. It causes painful lumps on the skin, high fever, swelling of lymph nodes, trouble moving, and a sharp drop in milk production. The disease spreads mainly through bites from insects like mosquitoes, ticks, and flies.

LSD IN INDIA

India reported its first confirmed LSD outbreak in 2019 in Odisha. The COVID-19 lockdown restricted its quick spread, but after that the virus quickly spread to many states. Things turned especially grim in 2022, when the disease hit cattle herds hard in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, and Jammu & Kashmir. That year, up to 80% of cattle in some areas fell sick, and the death rate among them reached a shocking 67%. This resulted in an estimated Rs 18,337 crore in losses and a 26% drop in milk output, seriously hurting the dairy industry and millions of small farmers who depend on livestock to survive.

At first, the government used an existing vaccine made for goatpox to protect the cattle. While it helped a little, it wasn’t perfect—it couldn’t fully protect animals and made it hard to tell if a cow was sick or just vaccinated.

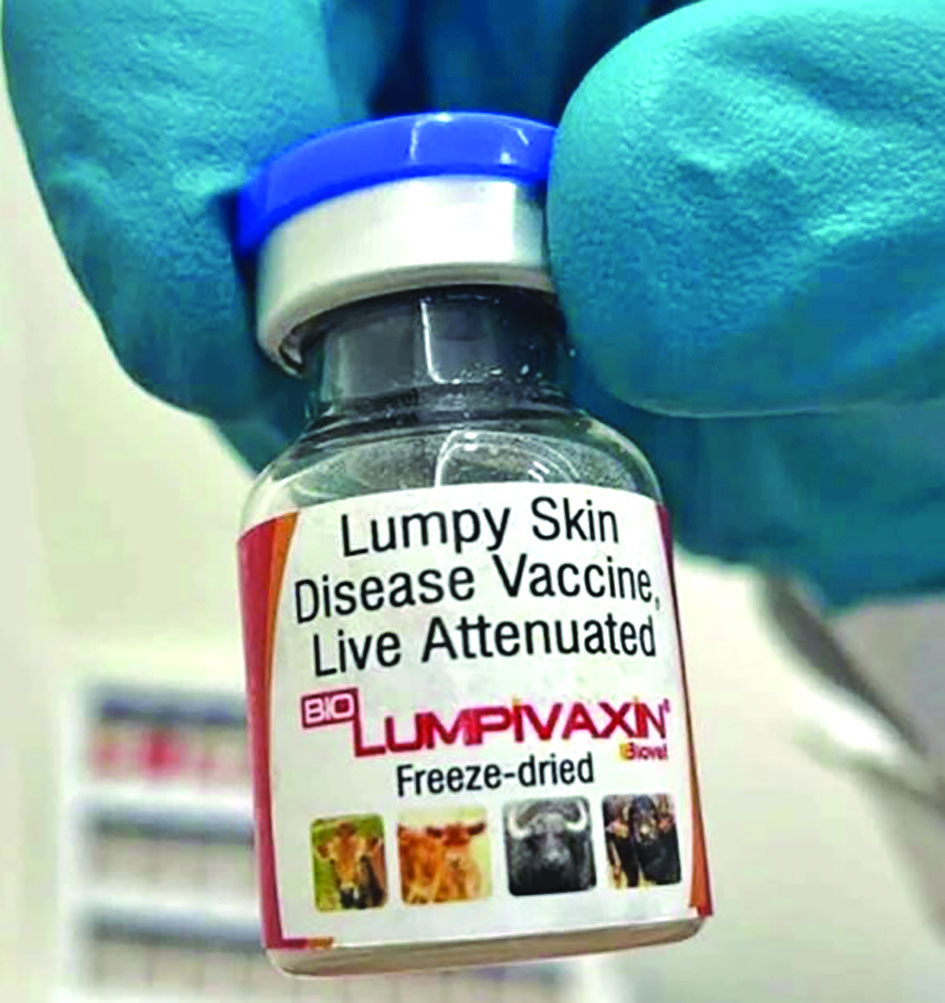

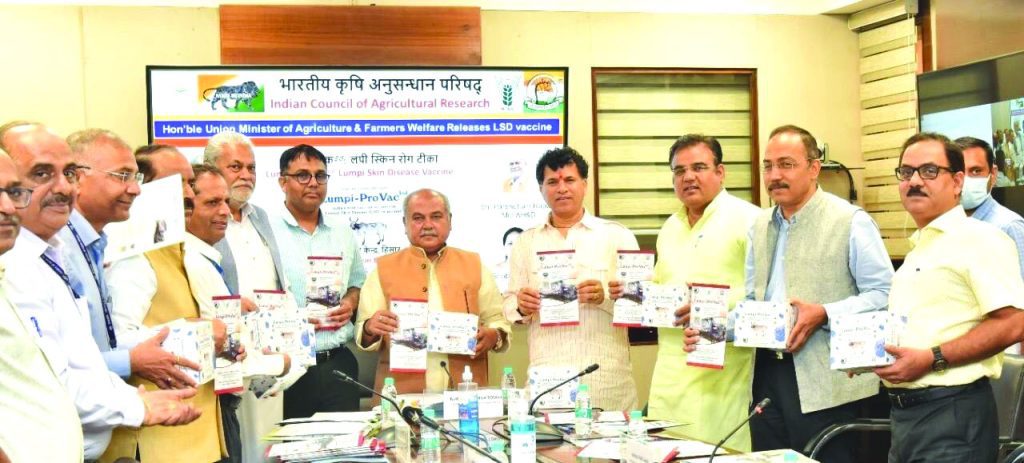

Realising the need for a better solution, a team of scientists led by this author at the ICAR-National Research Centre on Equines (NRCE) in Hisar, under the visionary leadership of Dr B N Tripathi, took matters into their own hands. They got to work on developing a special vaccine using an LSD virus strain found in Indian cattle. After carefully growing it through over 50 generations in the lab, they created a new, safer, and more effective vaccine called Lumpi-ProVacInd. Later, the vaccine technology was transferred to industry and the commercial product from Biovet India Pvt, a group of Bharat Biotech, is now available as BIOLUMPIVAXIN in the market.

Image Courtesy: PIB

Unlike some international vaccines that can cause side effects like fever, skin lumps, or temporary drop in milk yield (a condition known as the ‘Neethling effect’), India’s homegrown vaccine doesn’t have these issues. It is also the world’s only vaccine that can clearly distinguish between infected and vaccinated animals—a huge plus for monitoring and controlling outbreaks.

The development of Lumpi-ProVacInd is a proud moment for Indian science. It’s not just a vaccine—it’s a lifeline for farmers, a win for animal health, and a shining example of India’s push for self-reliance under the ‘Make in India’ and ‘Viksit Bharat’ missions. More than anything, it shows what can happen when science, dedication, and a passion to protect livelihoods come together. This vaccine is more than just medicine—it’s hope in a bottle.

SCIENCE BEHIND THE WORLD’S DIVA MARKER VACCINE

India’s first—and the world’s only—DIVA-compatible vaccine for LSD, represents a major scientific breakthrough (DIVA-Differentiating Infected from Vaccinated Animals). The vaccine features a deletion in the ORF154 (gene), which is present in wild-type LSDV but absent in the vaccine strain. Capitalising on this distinction, the team cloned, expressed, and purified the ORF154 protein from the wild-type virus and used it as a capture antigen in an ELISA test. This DIVA assay demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity, reacting only with sera from naturally infected animals—not vaccinated ones. This allows for accurate differentiation between infected and vaccinated animals, a critical advancement for disease surveillance and outbreak management, especially in endemic regions. By integrating this cutting-edge diagnostic tool with a potent live-attenuated vaccine, Lumpi-ProVacInd not only protects livestock but also places India at the forefront of global efforts in LSD control and veterinary vaccine innovation.

INDIA’S NATIVE CATTLE CARRY BUILT-IN ARMOR AGAINST LSD

During the massive LSD outbreak in 2022, not all cattle were affected the same way. While crossbred cows were hit hard, some native Indian breeds, like the hardy Rathi breed of cattle showed lower morbidity (13.75%) and case fatality rate (27.27%) as compared to the crossbred cattle (87.77% morbidity and 69.51% case fatality).

What’s their secret? According to scientists at the NRCE Hisar, it comes down to a tiny molecule in their blood called miR-29a. This molecule usually tones down a key immune booster called interferon-gamma (IFN-). But Rathi cattle naturally have lower levels of miR-29a, which allows IFN- to do its job better—boosting the immune system and helping the body fight off the virus more effectively. In simple terms, their bodies are wired to fight off the disease more strongly, thanks to this unique genetic advantage.

These findings highlight why India’s native breeds are so valuable—not just for tradition or hardiness, but for their natural disease resistance. This insight opens the door to using these breeds more in future breeding programmes and could even shape better vaccination strategies. In the race to protect our livestock, indigenous cattle might just be our strongest defence.

HOW A TINY MOLECULE COULD HELP DETECT LSD EARLY IN CATTLE

While studying how cattle respond to LSDV, scientists at the NRCE Hisar uncovered something fascinating. They found that a tiny molecule in the blood, called miR-29a, might hold the key to detecting the disease early—before the animal even shows any symptoms.

Here’s how it works: during the first week of infection, when the cattle might still look healthy, levels of miR-29a drop while another important immune molecule, called IFN-, goes up. This seesaw pattern could help vets spot the infection before it gets serious.

Even more interesting, when the immune cells in the blood were exposed to the virus in a lab setting, miR-29a levels dropped sharply. At the same time, the body’s defence system kicked in with full force—especially the virus-fighting CD8+ T cells—and managed to clear the infection.

Researchers found that if miR-29a levels dropped by 60% or more, it meant the animal had a strong immune response. This means miR-29a could also help predict how well a vaccinated animal will fight off the virus.

In simple terms, this tiny molecule might become a powerful tool—not just for early diagnosis, but also for checking if a vaccine is working. It’s one more step toward smarter, faster disease control for our livestock.

*The writer is Director, ICMR-National Institute of Virology, Pune. He was Principal Scientist at National Centre for Veterinary Type Cultures, Hisar (Haryana), where he along with a team developed Lumpi-ProVacInd.