Image Courtesy: Colossal Biosciences

International News

For decades, the dire wolf (Canis dirus) existed more in legends and pop culture, thanks to shows like the Game of Thrones, than in living reality. Thought to have gone extinct approximately 12,000 years ago at the end of the last Ice Age, dire wolves roamed across the Americas, preying on large herbivores like bison and horses. Their powerful build, greater than that of today’s gray wolves, made them formidable apex predators.

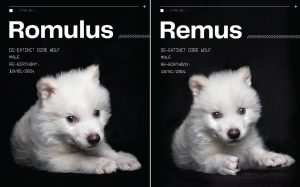

However, the once impossible has now become reality. Colossal Biosciences, a Texas-based biotechnology company, has announced the successful birth of three dire wolf pups—Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi. These pups are not clones, strictly speaking, but are instead the result of advanced gene editing techniques that modified the DNA of gray wolves to reintroduce traits associated with the dire wolf species.

GENE EDITING

Scientists first extracted ancient DNA fragments from dire wolf remains found preserved in tar pits and ice fields. After an exhaustive sequencing process, they identified fourteen key genes that contributed to the dire wolves’ distinctive characteristics—larger size, stronger jaws, and a more robust immune system, among others. Using CRISPR gene-editing technology, these genes were inserted into embryos of modern gray wolves. The edited embryos were then implanted into surrogate domestic dogs, leading to successful births.

Though the new animals carry many of the physical features of their ancient ancestors, experts caution that these are not exact copies. Because the complete dire wolf genome could not be perfectly reconstructed, these recreated animals are best described as ‘genetic approximations’ rather than full de-extinctions. Nevertheless, the achievement represents a massive step forward in the field of de-extinction and genome engineering.

Colossal Biosciences, co-founded by geneticist Dr George Church and entrepreneur Ben Lamm, has been at the forefront of de-extinction efforts. Their ambitious projects also include plans to bring back the woolly mammoth and the dodo. With the successful creation of dire wolf approximations, they have demonstrated the real-world potential of reviving extinct species—at least partially.

“Our mission was never just about recreating the past,” said Lamm during a press conference. “It’s about applying the best of genetic science to learn from ancient ecosystems and find new ways to protect current and future biodiversity.”

Scientists believe that understanding the dire wolf’s genetic makeup could offer insights into predator-prey dynamics, resilience to diseases, and climate adaptation—knowledge that could benefit conservation efforts for endangered species today.

IMPLICATIONS OF DE-EXTINCTION

However, not everyone is celebrating. Several conservationists and bioethicists have raised critical questions about the implications of creating genetically engineered proxies for extinct animals.

“What happens if these creatures, bred in labs, are released into ecosystems they no longer belong to?” asked Dr Sonia Ward, an ecologist at the University of California. “They could compete with existing species, spread unknown diseases, or suffer because they lack the cultural knowledge of true dire wolves.”

There are also ethical concerns about the welfare of the surrogate mothers used in these experiments, and the long-term health of the gene-edited pups. Colossal Biosciences has assured that all procedures were conducted under strict veterinary supervision, and the health of Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi will be closely monitored as they mature.

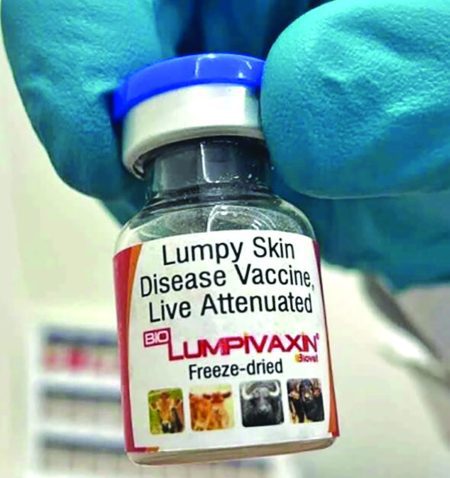

The dire wolf project is part of a larger movement sweeping through genetic science—using biotechnology to revive, or at least approximate, lost species. Recently, scientists in India announced a parallel breakthrough: the near-complete revival of extinct Indian cheetahs through gene editing.

INDIAN CHEETAH?

Using similar techniques, researchers at India’s Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB) and the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) collaborated with international partners to create embryos carrying traits from the original Indian cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus), which went extinct in India in the 1950s. These embryos are expected to be implanted into surrogate African cheetahs to create offspring that closely resemble the native Indian population.

The effort follows India’s broader initiative to reintroduce cheetahs into the country’s grasslands, beginning with African cheetahs imported from Namibia. Gene technology offers the tantalising prospect of restoring the true Indian lineage—a goal once thought impossible.

Dr Raghav Sharma, part of the CCMB project, remarked, “We are not just bringing back the physical form, but restoring a lost part of India’s ecological and cultural heritage.”

The successful births of dire wolf pups and the progress in reviving Indian cheetahs mark a turning point. De-extinction is no longer a fringe idea but an emerging reality.

Supporters argue that these technologies could help reverse some of humanity’s most tragic ecological mistakes. By restoring lost species—or at least their ecological roles—we might be able to repair damaged ecosystems, increase biodiversity, and build resilience against climate change.

Yet critics warn of unforeseen consequences. Introducing new or “resurrected” species could disrupt food webs, lead to hybridisation with existing species, or create ethical dilemmas around conservation priorities.“Just because we can bring back an approximation of an extinct animal,” Dr Ward cautions, “does not mean we should, without fully understanding the consequences.”

Even among scientists working on these projects, there is an acknowledgment that de-extinction must proceed with caution. As Dr George Church himself has said, “We’re treading into unknown territory. It’s vital we proceed with humility, thorough scientific scrutiny, and open public dialogue.”

For now, Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi remain in a secure research facility in Texas, where they are being carefully observed. Colossal Biosciences plans to study their development, health, and behaviour over the coming years before making any decisions about broader breeding programmes or potential semi-wild habitats.

There are no immediate plans to release the animals into the wild. Instead, the focus will be on long-term genetic studies, learning about ancient traits, and exploring how such knowledge could help conserve modern canid species (comprising dogs, wolves, coyotes, jackals and foxes) under threat.

In the meantime, the pups have already captured the public imagination. Images of the fluffy, powerful-looking pups have flooded social media, sparking everything from scientific debates to fan art and comparisons to their fictional counterparts from the Game of Thrones.

The birth of the dire wolf approximations is a symbolic moment—where ancient DNA, modern technology, and human ambition have converged. Whether this leads to a new golden age of conservation or a Pandora’s box of ecological risks remains to be seen.

What is clear, however, is that science has crossed a new frontier. The howl of the dire wolf, silent for millennia, has found its echo once again—not just in labs, but in the collective imagination of a world grappling with legacies of extinction and promises of revival. As Dr Church eloquently put it, “The past is not dead. In a very real sense, it’s alive—inside our genes, our dreams, and now, inside the living creatures that carry the spark of a lost world.”